Some Rules for Administering a Special Assessment

During their career, many certified assessment administrators will be faced with the task of participating in the creation of a special assessment and apportioning eligible costs. Unfortunately, rules related to these processes are complex and hard to find because they are dispersed between statutory guidelines and judicial decisions. The purpose of this article is to outline some fundamental rules gathered from those sources. Putting important rules in one location will hopefully create a useful reference. It may reduce the possibility of misunderstandings and mistakes which can lead to rancorous public hearings and costly defense before an appellate body.

Special assessments are always a unique power delegated to a taxing jurisdiction. Consequently, they are limited specifically by the act which enables the creation and levying of each special assessment and restrictions found in decisions of Michigan’s superior courts. In one aspect, cities are given more latitude than other jurisdictions. They can pass ordinances which create a special assessment process. Jurisdictions not granted the right to create a special assessment procedure simply follow a specific statute.

There are too many laws which enable a special assessment levy to list here. However, there are categories of enabling legislation that can be mentioned. One is legislation specific to common forms of infrastructure such as water, streets, sidewalks and sewage systems. They are utilized by jurisdictions such as cities, counties and townships. Another category is laws specific as to function. An example is the Lake Improvement Act ( Part 309 of 1999 PA 451) which provides ways to keep lake waters clean. These examples, and most special assessments levied in Michigan, are levied under the state’s “tax laws” and are appealed to the Michigan Tax Tribunal.

Special assessments levied pursuant to the Drain Code (1956 PA 40), the inland Lake Level Act (now part 307 of PA 451 1994) and similar laws, are authorized under the concept of a government’s “police powers.” An appeal from this form of act is made to a court of law.

Because 1954 PA 188 ( Public Improvement Act for Townships) is so commonly used in the state, specific references will be made to it as part of this article. Irrespective of that focus, the rules articulated apply to all special assessments.

Definition of a Special Assessment

“A special assessment is not a tax. Rather, a special assessment ‘is a specific levy designed to recover the costs of improvements that confer local and peculiar benefits upon property within a defined area.’” Kadzban v City of Grandville, 442 Mich 495, 502; 502 NW2d 299 (1993). Special assessments are ‘sustained upon the theory that the value of property in the special assessment district is enhanced by the improvement for which the assessment is made.” Knott v City of Flint, 363 Mich 483, 499; 109 NW2d 908 (1961). Municipal decisions regarding special assessments are generally presumed to be valid. In re Petition of Macomb Co Drain Comm’r, 369 Mich 641, 649; 120 NW2d 789 (1968). A ‘special assessment will be declared invalid only when a party challenging the assessment demonstrates that ‘there is a substantial or unreasonable disproportionality between the amount assessed and the value which accrues to the land as a result of the improvements.’” Kadzban, supra at 502, quoting Crampton v Royal Oak, 362 Mich 503, 514-516; 108 NW2d 16 (1961). The party challenging the special assessment also has the burden of establishing the True Cash Value (‘TCV’) of the property being assessed. MCL 205.737 The TCV is equivalent to fair market value, CAF Investment Co v State Tax Comm, 392 Mich 442, 450; 221 NW2d 588 (1974), and is defined as ‘the usual selling price at the place where the property to which the term is applied is at the time of the assessment, being the price that could be obtained for the property at private sale ...’ MCL 211.27" (Rema Village Mobile Home Park v Ontwa Twp)

“A special assessment starts with a need”(Michigan Training Manual, Section 3, pg 13-6 ) There are two fundamental principles which control the levying of a special assessment; necessity and benefit. Necessity is an amorphous concept, not clearly defined by the courts, but the courts have provided guidance on the concept. One element of “necessity”is that the jurisdiction attempting to fund the public improvement must formally “find” or “determine” by resolution there is a public need which makes the improvement, not simply convenient or desirable, but “necessary.” While challenges to the “necessity” of a public improvement have been rare, there are some. For example, the Supreme Court ruled that the improvement actually made, had to be the same improvement that was deemed “necessary.”

“Undoubtably the common council should not make a different improvement from the one declared necessary.” (Kuick v Grand Rapids, 590)

Furthermore, the proposed public improvement must be determined or found “necessary” pursuant to terms of the authorizing statute to advance a project. Ruling on a special assessment under the Inland Lakes Act, the Supreme Court stated that a resolution of necessity by the appropriate authorities of a jurisdiction is a jurisdictional requisite to the process.

“A definite determination of need for that purpose and of the normal shore line or ‘natural height and level’ of such lake is made the basis for all which follows. Not only did the board of supervisors fail to find the natural level, but it made no declaration that any action to that end was necessary “in order to improve or maintain navigation thereon, or to promote public health or welfare.”...”A resolution of determination within the purpose of the statute was a jurisdictional prerequisite to further proceedings...this case must be reversed for the foregoing reasons...” (Niles v Meeker, 368)

The courts have also contemplated the term “necessary” with regard to which properties were to be included within the special assessment district. In a dispute over levying a special assessment on certain lands for the maintenance of a shopping mall, the court found that the lands in question were necessary to accomplish the statutorily permitted maintenance and operation of the mall; since they were actually located within the enclosed mall.

“It is essential to note two important facts. First, the lands on which the city has levied a special assessment comprise an integral part of the enclosed mall itself and thus are without doubt, ‘lands necessary to accomplish the foregoing’, e.g. lands necessary to accomplish the construction of a mall with bus stops, information centers and other buildings serving the public interest. Without the stores there would be no mall.” (McIntosh v city of Muskegon, 511)

In summary, a finding or determination of necessity “within the purpose of the statute is a jurisdictional prerequisite to further proceedings”; the public project completed must be the same project as the jurisdiction determined necessary; and “lands necessary to accomplish”...”serving the public interest” should be included within a special assessment district. The term necessity implies a need greater than a mere convenience or want or desire. It also conveys a sense of immediacy, something that cannot be put off for long. Act 188 requires this determination at M.C.L. 41.724(1). “Upon receipt of a petition or upon determination of the township board if a petition is not required...”

Land is basis for benefit; ad valorem levy exception

The special assessment, throughout its history, is an assessment placed upon only real estate (not personalty) and with limited exception levied only against the land which is benefitted by an improvement. Various courts have referenced the requirement for a levy upon land. Notice the use of the term “land” in these quotes.

“The advantage may be the same to 2 lots side by side, although one lot may be improved, and of much greater value than the other. The cost of local improvements is not assessed according to the value of the property. The assessors are not to determine the increased valuation of the district by reason of this improvement, nor the value of this improvement to the district, for that has been fixed by the council. They are simply to apportion a fixed amount, not with reference to values alone, but also with reference to needs, necessities and advantages.” (Crampton v City of Royal Oak, 521)

“The intrinsic value of a vacant lot may be increased much more in proportion , than one occupied with valuable buildings; so that an apportionment based upon the value of the premises might, and probably would, operate unjustly and inequitably.”(Williams v City of Detroit, 9)

“Rather, a special assessment will be declared invalid only when the party challenging the assessment demonstrates that ‘there is a substantial or unreasonable disproportionality between the amount assessed and the value which accrues to the land as a result of the improvement.” (Kadzban v city of Grandville, 502 )

“we clarified the test for determining the validity of special assessments. An earlier Court of Appeals opinion suggested that there were three alternative bases that would support a finding of special benefits sufficient to justify a special assessment: 1) an increase in the land’s value, 2) relief from some burden to the land, or 3) the creation of a special adaptability of the land. Rejecting this approach, this Court said that special assessments are permissible only when the improvements result in an increase in the value of the land specially assessed.”(Kadzban v City of Grandville, 501)

Act 188 specifically limits the assessment to the land.

“After finally determining the special assessment district, the township board shall direct the supervisor to make a special assessment roll in which are entered and described all the parcels of land to be assessed, with the names of the respective record owners of each parcel, if known, and the total amount to be assessed against each parcel of land, which amount shall be the relative portion of the whole sum to be levied against all parcels of land in the special assessment district as the benefit to the parcel of land bears to the total benefit to all parcels of land in the special assessment district. MCL. “41.725(1)d.

An exception to the rule that land is the basis for the assessment is the ad valorem special assessment. The passage of 1951 PA 33 and a Supreme Court ruling in St Joseph Twp v Municipal Finance Comm, 351 Mich 524; 88 NW2d 543 (1958), added a new version of special assessment. It has a millage rate levied against the “taxable value” of the property. A unit-wide special assessment district was upheld along with the SEV of the property assessed becoming the measure of benefit to that property. A vote of the people is usually required to authorize the “ad valorem” special assessment. Today there are over 100 unit-wide assessments in the state.

“Benefit” used in the context of the special assessment means one thing, an increase in the market value of a property as a unique, direct and measurable result of the public improvement for which the special assessment is to be levied. The Michigan Supreme Court defined the term “benefit” in this way:

“In order for an improvement to be considered to have conferred a special benefit, it must cause an increase in the market value of the land.” (Ahearn v Bloomfield Twp, 493)

“we clarified the test for determining the validity of special assessments. An earlier Court of Appeals opinion suggested that there were three alternative bases that would support a finding of special benefits sufficient to justify a special assessment: 1) an increase in the land’s value, 2) relief from some burden to the land, or 3) the creation of a special adaptability of the land. Rejecting this approach, this Court said that special assessments are permissible only when the improvements result in an increase in the value of the land specially assessed.” (Kadzban v City of Grandville, 501)

The measurement of “benefit” is critical to the special assessment process. Whereas there may be several methods of apportioning the costs (per front foot, per lineal foot, by acreage et cetera) there is only one measure of benefit under Michigan’s laws. The key is properly designing the method to reflect market value.

Those measuring “Benefit” must rely upon the definition of market value and legal, economic and scientific facts associated with value in exchange. For example, special assessments must consider elements of “highest and best use.”

“Without discussing the issue in detail, it is clearly the settled law of this state that in determining whether a property is benefited by a particular improvement the inquiry is not limited to the present use of the property but, rather, to uses to which it may be put, including such as may be rendered more feasible by the carrying out of the project in connection with which the assessment is levied.” ( Crampton v City of Royal Oak, 518)

The apportionment process may use any of a number of methodologies to discover factually how the “benefit” is propagated from the public improvement. An example would be that a sidewalk or roadway is assessed per lineal foot of frontage; or the costs of a highway noise suppression berm is apportioned based upon scientific evidence of where sound waves have been best suppressed by the berm; typically an intermittent pattern not related to distance from the berm, but instead from how sound travels after hitting the berm. (Michigan Training Manual, Section 3, pg 13-9)

Residential properties in quiet and peaceful neighborhoods have an amenity value greater than that of similar properties subject to noise from traffic or runway approaches or any of a number of noise generation scenarios. To determine benefit, the idea is, how do buyers and sellers incorporate benefit from the public improvement within a property’s price. In the case of potable water and sewage services the benefit does not have the gradient issue that a few extra feet of frontage does or that an attenuation of noise by 1 decibel or 3 decibels presents.

Water and sewer services are examples of “either or” benefit patterns. Either the property has the service or it must be acquired. Benefit is predicated on the cost of acquiring the least expensive, acceptable service. If there is service, but it is deficient so that it needs to be repaired or replaced, then the value to prospective buyers and sellers is the cost of the repair or replacement. Economic principles used to interpret actions of buyers and sellers in such situations are “substitution,” “contribution” and “competition.” Thus, an evaluation of “benefit” in the special assessment process requires an interpretation from the perspective of buyers and sellers in the appropriate real estate market, if the court’s mandate of market value is to be accomplished.

“The assessors, not the court, weight the benefits, if, in truth, there are benefits to be weighed.” (Fluckey v Plymouth, 454)

“The assessors are not to determine the increased valuation of the district by reason of this improvement, nor the value of this improvement to the district, apportion a fixed amount, not with reference to values alone, but also with reference to needs, necessities and advantages.” (Crampton v City of Royal Oak, 521)

Facts must be used as the basis for determining benefit, costs eligible to be assessed, the Service District and the Special Assessment District. A fact is“a truth known by actual experience or observation” (American College Dictionary, 431) Decisions required in the special assessment process must be fact based. It is not enough to simply look at some facts or facts easy to find. When factual information is available, it is expected to be used by those with competency in special assessment administration. From the earliest days of assessment administration in Michigan, courts have invalidated a special assessment where facts, both known and ascertainable, were not used in decisions.

“So a law directing such an assessment as the commissioners should deem “just and equitable” was held unconstitutional because it did not direct the fact to be found that the property was benefited to the amount of the tax to be imposed.” ... “Applying this rule to this act, it must be declared void. It contains no provision which requires the assessment based upon the local district to be in proportion to the benefits received.” (City of Detroit v Chapin, Judge, 590-591)

“From this and other testimony we feel obligated to agree with the trial judge in the conclusion that the boundaries of the district were fixed by the common council without reference either to known or ascertainable facts; that the action was arbitrary and unwarranted. We are of opinion, also, that the bill of complaint, fairly interpreted, charges the creation of a district invalid because not including lands benefitted by the improvement.” (Lawrence v City of Grand Rapids, 143)

Categories of Facts: Legal, Economic and Scientific (L.E.S.)

Instructions from the most recent text on special assessment administration used in classes for assessors seeking recertification (or those persons seeking certification) contains language on the use of “facts” in the assessment process. The language which follows explains three categories of facts recommended as the minimum for distinguishing between properties that should be assessed and those that should not. It refers to identifying properties which belong in the Special Assessment District from those that are merely connected somehow to the public improvement. The geographic area in which properties are somehow connected to the public improvement is known as a “Service District.” It is from the Service District that the Special Assessment District is carved:

Once you’ve examined all documents related to the finding of necessity, you should seek out a possible pool of information that may be available for analysis. At a minimum, the source of facts used to define boundaries for a Service District should include considerations of legal, economic and scientific (LES) information that may be available. (Reschke and Turner, 59)

In the administration of special assessments, an apportionment is the process of allocating costs that are eligible to be specially assessed, to the individual properties or entities to be assessed based upon benefit or other statutory requisites. The statute authorizing a specific project will direct the apportionment. The apportionment directive in 1954 Act 188 is found at MCL 41.725(1)d.

“the total amount to be assessed against each parcel of land, which amount shall be the relative portion of the whole sum to be levied against all parcels of land in the special assessment district as the benefit to the parcel of land bears to the total benefit to all parcels of land in the special assessment district.”

Costs to be apportioned: Eligible and ineligible

Some costs may not be eligible for the special assessment levy period. Others may be eligible, but cannot be assessed to specific properties. These are assessed at large. Therefore, there are two categories of determination with regard to a determination of eligible costs: (1) costs that are eligible for apportionment must be separated from those that are not; and (2) of costs that may be apportioned, there must be a separation of those to be apportioned “at-large” and those to be apportioned to individual parcels.

“Before noticing the distinction urged by counsel upon the argument, it seems proper to remark that every species of taxation in every mode, is in theory and principle, based upon an idea of compensation, benefit or advantage to the person or property taxed, either directly or indirectly.” (Williams v City of Detroit, 7)

Assessors are taught to use indirect benefits as the first step in the apportionment process.

“The first step in any special assessment project is to establish the service district when determining the benefit method.”(Michigan Training Manual, Section 3, pg 13-6 )

Assessment administrators look to see how land is somehow connected to the public improvement. For example, in the case of an impoundment that creates a lake, one connection is the area from which water drains to the lake and the area downstream to which flooding would occur if the dam were to break. In the case of a parking deck, one connection would be the area to which patrons of stores or other services will walk and from which local employees using the deck will arrive. In the case of an economic development project which serves tourists, one of the connections would be vehicular travel routes within the local economy along which tourists will buy services and product.

Once the geographic distribution of all benefitting properties is identified using legal, economic and scientific facts (e.g., drainage, flooding, convenient parking, new revenue, elevated tax collections et cetera), the universe of potential properties for a special assessment district has been identified.

A geographic distribution of benefits from a public improvement may be analyzed by first figuring out exactly which benefits exist. While these benefits must contain economic components, it would be unusual if there were not other “benefits” besides economic. Other benefits might include: public safety components, public welfare components, a larger tax base or other benefits to specific political jurisdictions, benefits to the environment and other benefits. The geographic extent of all benefits from the improvement defines the “service district. (Reschke and Turner, 58)

The Service District is a beginning point for the economic analysis required to demonstrate a change in market value of properties to be specially assessed. It defines the universe of benefitting properties. It serves to assure that properties which should be specially assessed are considered for inclusion within the S.A.D. From that universe of somehow connected properties emerge those properties which receive direct, unique and measurable increases in their market values. This makes them eligible for inclusion within the special assessment district. The boundary between properties which have some form of benefit (connection) to the public improvement and those with none geographically defines the Service District.

Special Assessment District (S.A.D.)

A special assessment district (S.A.D.) is a geographic area within a Service District. It has a boundary delineated by the junction between those properties which are eligible for a special assessment levy because they receive a measurable, direct and unique enhancement in their market value as a result of some pubic improvement, and those properties which do not benefit in the same way. Such districts must be determined using competent, material and substantial evidence based upon fact.

“It is the duty” of an entity “when a special improvement is made, the benefits accruing from which are regarded as local, to determine the boundaries of the district within which the property is supposed to be specially benefitted by the improvement...The carving out of a special assessment district in a city is a practical matter, depending wholly upon facts.” (Lawrence v City of Grand Rapids, 136)

Properties somehow connected to a public improvement which do not receive the peculiar, specific, direct increase in value above that which the general public receives, are said to be “indirectly benefitted.” In addition, there are costs that exceed limits created by benefit and costs for ancillary work that may not be specially assessed. Costs and expenditures for a project that may not be specially assessed are to be paid by the government unit enabling the special assessment. Examples of costs that may not be specially assessed include money spent for infrastructure, planning or engineering work on property outside the S.A.D.; costs incurred before there was a project; costs for “oversized” infrastructure (e.g., a 12-inch water main needed to extend water to an area of future growth when an 8-inch main will serve the S.A.D.).

“When a property lies within a jurisdiction empowered to levy special assessments for public improvements and an improvement is made for the public good, the cost of which cannot be levied against a specially benefitting property, the property is deemed to receive an indirect benefit and may not be specially assessed. The portion of the cost of the public improvement charged to indirectly benefitting properties is termed an “at-large” special assessment.”(Reschke and Turner, 71)

“According to a number of Authorities, if the expense of a local improvement exceeds the special benefits, then the city at large should bear the excess, or in any event, a portion of the burden.” ... “Frequently, the amount of special assessments cannot be known until laid, and hence, the net amount to be paid by those specially benefited, and the amount remaining to be paid by the city, cannot be ascertained until that time; no apportionment of the share to be paid by the city can therefore be made until after the assessments are laid.”(70 Am Jur 2nd)

“The special assessment cannot be justified on the basis of public health needs and the tribunal erred to the extent it did so. ... Here, public health benefits from the implementation of a municipal sewer system are not unique to the assessed property. Such benefits inure to the community at large. Because the property did not increase in value as a result of the municipal sewer system that was the subject of the special assessment, the improvement did not confer a special benefit to the assessed property as a matter of law.” (Rema Village Mobile Home Park v Ontwa Twp)

Valid project costs can have both direct and indirect components. An example is infrastructure “oversized” (extra capacity) to service future growth or areas outside the S.A.D. Costs equivalent to what is specifically needed for “standard service size” to a property are specially assessed. Costs for components exceeding the standard size (and engineering and other professional fees charged to plan the oversized components) are assessed at-large. (Michigan Training Manual, Section 3, pg 6-7) The same thing is true geographically. Costs associated for work within the S.A.D. are specially assessed; those for areas outside are at-large. Another example relates to political boundaries. Some statutes permit one unit of government to tax another unit of government (See Part 307 of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act). Under such circumstances an assessment may be based upon the government parcel within the special assessment district. Generally, one government may not seize another’s for non payment of the tax, there is no lien against the land for nonpayment and the payment is at-large.

Formula

Legislation may contain specific formulas for apportioning costs. The Act 188 apportionment formula may be stated as:

Propertyassment = (PropertyBenefit/S.A.D.Benefit)*Eligible Costs

Let’s use that formula to create an apportionment example. Assume total project costs eligible to be assessed against all parcels in the S.A.D. is $3,000,000. Assume there are 250 parcels and the benefit per parcel is estimated at $7,000 per parcel.

The total benefit for the S.A.D. can be estimated as 250 times $7,000 or $1,750,000. Continuing with the assumption an individual parcel has a benefit of $7,000, then, the special assessment against one parcel would be equal to ($7,000/$1,750,000) times $3,000,000 or $12,000.

In summary, we end up with an increase in market value for a parcel (benefit) of $7,000 and a special assessment against the parcel of $12,000. The tax burden in this case is 1.71 times the benefit.

As we will see, there is a judicially mandated test for “reasonableness” that should be used to test whether or not the assessment calculated using the statute’s formula, is “reasonable” with respect to one court’s decision. If it is unreasonable, then the jurisdiction must lower it to a reasonable level or an appeal may be sustained. That is, the MTT or a court may reject the assessment, even though mathematically, it was calculated correctly.

It may be worth noting in the example given above, the total “benefit” estimated for the S.A.D. was $1,750,000; an amount not equal to the costs eligible to be assessed ($3,000,000). There is $1,250,000 more cost than benefit.

It is not uncommon to find the sum of the estimate of benefit for the S.A.D. is less than the costs of the project. A simple formulaic analysis such as that shown, provides a warning there may be an at-large assessment of $1,250,000.

Summarizing the steps leading up to an apportionment:

For an apportionment to be made, there must be a public project (sometimes called an improvement). The project must be found to be “necessary” by the appropriate legislative authority. The project must create “benefit” which is geographically disbursed. The benefit may be “indirect” or “direct.” Only properties receiving a measurable (more than a de minimus) direct benefit may be specially assessed. “An assessment cannot be sustained where the benefit from the improvement is merely speculative or conjectural; it must be actual, physical and material.” (70 Am Jur 2d, § 21 pg 862) Usually public lands are exempt from a special assessment, but there are circumstances where one government unit may specially assess another.

When private property is to be assessed, the determination of benefit in most legislation is based upon the value of land and not upon a value consisting of the land plus improvements to the land. Including the value of the improvements is permitted in the ad valorem special assessment. There, a millage rate is equally applied to each property being assessed and the special assessment equals the millage rate times the taxable value.

Summarizing the apportionment of eligible costs

Following initial steps to create a project several things must happen to begin an apportionment of eligible costs and create the roll. There must be a decision as to which properties should be specially assessed. The pool of possible properties is found in the Service District. From it is carved the Special Assessment District. There must be a separation of “eligible” costs that may be assessed from “ineligible” costs that may not be assessed. Of the eligible costs, those to be assessed “at-large” must be separated from costs that can be specially assessed against properties comprising the Special Assessment District (S.A.D.). For a valid apportionment to occur, a method must be established that reasonably and justly apportions costs based upon changes in a specific property’s market or true cash value.

The method of apportionment may vary from circumstance-to-circumstance, but whatever the method; it must be implemented in such a way, that the apportionment and benefit are measured in U.S. dollars because upon completion of the apportionment, there must be a reasonably proportionate ratio between the apportioned costs and the benefit measured. While a dollar of assessment per dollar of benefit is a goal, a reasonable apportionment may exceed that relationship. Where the variance is too great, the assessment will be invalid.

“To be valid, a tax or special assessment shall be levied in accordance with some definite plan designed to bring about a just distribution of the burden. Thomas v Gain, 35 Mich 155, 24 Am.Rep.535; Panfil v City of Detroit, 246 Mich 149, 224 N.W.616,618;Wood v Village of Rockwood, 328 Mich 507, 44 N.W. 2d 163.” (St. Joseph Twp v Mun. Finance Comm., 533)

“While we certainly do not believe that we should require a rigid dollar-for-dollar balance between the amount of the special assessment [426 Mich 403] amount of the benefit, a failure by this Court to require a reasonable relationship between the two would be akin to the taking of property without due process of law. Such a result would defy reason and justice.” (Dixon Rd v Novi, 216-17)

A review of the method of apportionment to assure the method is reasonable and just should be conducted. First, costs charged, must be valid costs. Costs incurred by the jurisdiction before there is legislative action to create the project cannot be a financial burden to the few who will bear the special assessment burden. Second, costs which should rightfully be assessed at-large must be excluded from the costs to be apportioned. Third, the method of apportionment is governed by the principle that “benefit” (an increase in market value in the property to be assessed caused directly and uniquely from the public improvement) must control the amount apportioned. Fourth, a method of apportionment must correspond reasonably to known and ascertainable economic facts. Finally, there must be a method of comparing the proposed financial burden to the estimated change in market value (benefit) to test for reasonableness. Without reasonableness, the apportionment “would be akin to the taking of property without due process of law.” (Kadzban v Grandville, 501-02)

The Residential Equivalent Unit (REU) is a term found from time-to-time in various special assessments. The REU often equates in some manner to water flow rates or a quantity of sewage effluent or whatever improvement product the REU is utilized for. An apportionment is then developed per parcel by dividing project costs by the total number of REUs, then delegating an REU count to each parcel. The final apportionment is the cost assigned per REU times the number of REUs assigned to a specific parcel. The REU method should be used cautiously because it is often performed without the assistance of an assessor and can be successfully challenged as improper in a number of ways.

For example, in apportioning costs for a recent water project, engineers defined an REU to equate to approximately three hundred gallons of water being used daily. The township identified a specific number of REUs per parcel based upon the improvement (e.g. a single family home was assigned one REU, a duplex was assigned two REUs and so on). Total project costs were divided by the total number of REUs within the S.A.D. The result was an REU computed as approximately $17,000. Thus, an assessment roll was generated in which properties improved with a single family residence were charged about $17,000, duplexes $34,000 et cetera.

There was a challenge to this methodology. The challenge alleged that the method was arbitrary and violated the law. The violation charged was that the method of apportionment did not relate at all to market value. Instead, it related to water flows without any consideration for the change in market value (benefit) a water service would provide to specific parcels of land. The dispute contained other allegations of impropriety. Upon challenge the jurisdiction terminated the project. An unfortunate and costly situation.

In examining engineering records an alternative method of tying the REU to market value was proposed. It was discovered that the cost of water main installation was approximately $41 per lineal foot. It was also discovered that new water wells had recently been installed on parcels to which municipal water lines were going to provide service. The wells cost between $7,000 and$10,000 to complete. It also was discovered that zoning regulations for residential properties defined buildable lots as having a minimum frontage of 175 feet.

Had the apportionment been based upon the project cost of $41 per lineal foot times 175 feet for the zoning “standard,” the apportionment would have been about $7,200 per property. That apportionment fits within the $7,000 to $10,000 range of actual costs for new well water service within the S.A.D. Had the jurisdiction adopted a method based in the facts just recited and thus, tied the apportionment to market value, there might have been a different outcome. The suggested technique moved the apportionment methodology from a cost-based distribution based upon water flow, to a market-based apportionment per residential unit, founded upon actual economic facts and giving a first impression of being reasonably related to benefit.

The change in determination of the REU may have had another advantage. Because there was such a difference between a residential REU based upon a front foot cost and the REU developed by simply dividing costs by the number of REUs, the jurisdiction would have been alerted to a potential at-large assessment of $9,800 per parcel; an over $1 million burden for the jurisdiction that was not counted on.

For a cost to be eligible to be specially assessed there must be a project pursuant to some enabling legislation and the cost must have been incurred after the project officially began pursuant to the enabling act. In this context, “be a project” means whatever steps the enabling legislation requires for commencement of activities. In some cases, there is a petition by taxpayers. In other cases, a board or authorized body must make a declaration, determination or finding. Timing dictates costs which are to be paid. The at-large (not eligible to be specially assessed) must be distinguished from those that are eligible to be levied as a special assessment tax. Such rules are binding upon the government units and require specific actions.

The “making of an assessment roll and apportioning a tax under the ordinances is a ministerial duty, and the confirmation of the assessment partakes more of the character of a judicial than a legislative act. We must, therefore regard the ordinances relating to assessments, as binding and obligatory upon the corporation as upon the individual citizens.” (Williams v Mayor of Detroit, 5)

The special assessment burden - Reasonable proportionality

There are two potential tests of proportionality. The enabling act may have a mandated formula. Within the Drain Code, when there are multiple jurisdictions involved, the formula is based upon the relationship between the SEV of the jurisdictions subject to an assessment. As we saw earlier, Act 188 contains a specific formula for determining benefit and the township supervisor is directed to create a special assessment roll with amounts assessed based upon the formula. MCL 41.725(1).

Jurisdictions have gotten into trouble for establishing a process whereby total eligible costs are simply divided by some number without regard to a benefit formula contained in the authorizing legislation. Other jurisdictions have apportioned costs as a some “flat” amount without regard to benefit. There are examples of Supreme Court decisions invalidating assessments of that nature. An assessment method that does not comport with the enabling law can be easily challenged. The rule is, use formulas within the enabling act, but not formulas that apportion without regard to a change in market value.

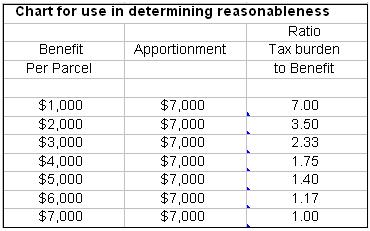

The second test is required by the Supreme Court in its Dixon Road decision (1986). The court acknowledged that a one dollar of assessment for one dollar of benefit is a goal, but there could be reasonable variation. The court did not set specific guidelines but invalidated an assessment with a burden 2.6 times the benefit. While the court sets the rule that there must be reasonableness, it is the MTT with its expertise, that may judge exactly what is a reasonable ratio. On appeal, the courts will intervene where it can be demonstrated a burden is not reasonably proportionate. The chart is included to illustrate a simple relationship between a $7,000 per REU assessment and various levels of benefit projected from market studies. At what point do you believe the apportionment become unreasonable if the perfect ratio should be $1.00 of assessment for every $1.00 of benefit?

Many jurisdictions are short of cash and exploring special assessment options. There are more than 100 unit-wide ad valorem special assessments in effect today. Special assessments are difficult to appeal, but given current economic circumstances, the probability of an appeal is far greater today than it was a few years ago. So, it is important to focus on the value of the land being assessed and the cost of the improvement. The increase in market value derived from a costly public project may not support moving forward with a project. It is important to examine the necessity of a project. If the “people” initiate a project requiring a tax burden via a petition signed by property owners, attitudes are quite different than when a government unit, on its own volition, declares the need for a tax burden on citizens. With the abundance of foreclosures and tax reverted properties, the potential for significant “benefit” being derived from a public project has been muted in a way different from a generalized reduction in property values due to economic conditions. The abundance of alternative properties within a market creates an opportunity to substitute an unburdened property for the specially assessed property. “Substitution” makes the special assessment burden more onerous and properties so burdened less desirable.

Though involving millions of dollars, the special assessment remains an obscure area of practice within the realm of property taxation. Leaders of taxing jurisdictions would be wise to seek the counsel of their assessor before moving forward with a project. The assessor has an opportunity to help a jurisdiction avoid costly mistakes in this complex process. A check list follows that may help summarize important steps of a special assessment process.

Sample checklist for a special assessment process

1. Identification of Enabling Act

2. Date process began with either a citizen petition or administrative determination of necessity

3. Identify date individual costs were incurred for project

4. Identification of specific public improvement

5. Is the improvement a required function of the jurisdiction, or just a desirable improvement?

6. Assemble legal, economic and scientific facts (L.E.S.)

7. How does the public improvement create value in real estate (make lots buildable, marketable, reduce street dust, eliminate highway noise, safe walking conditions for pedestrians et cetera)

8. How does the value spread from the public improvement? Only adjacent lots, tiers of lots (e.g. lakefront, deeded access to water or easy access to water), in an irregular pattern?

9. Develop Service District

10. Develop Special Assessment District (consistent with benefit identification, lot lines, specific distance from improvement (e.g. sewers, water mains, street surface et cetera)

11. Develop method of apportioning costs that is consistent with buyer/seller behavior: e.g. front foot, acreage, distance, sound levels, unit or per lot et cetera

12. Separate Eligible costs from ineligible costs (timeliness, outside district et cetera)

13. Separate at-large costs from locally assessed costs (over capacity; public areas, exempted properties et cetera)

14. Use apportionment method to apportion costs

15. Test reasonableness as compliance with statutory guidelines

16. Test reasonableness of tax burden to benefit

17. Create and announce roll, hold hearings, adjust if necessary, confirm roll

18. Whew !! Go on vacation

References:

Ahearn v Bloomfield Twp, 235 Mich App 486; 597 NW2d 858 (1999)

The American College Dictionary, 1960 Random House, New York (1960)

Crampton v City of Royal Oak, 362 Mich 503; 108 N.W. 2d 16 (1961)

City of Detroit v Chapin, Judge 42 L.R.A.638, 112 Mich 588; 71 N.W.149 (1897)

Dixon Road Group v City of Novi, 426 Mich 390; 395 N.W.2d 211 (1986)

Fluckey v Plymouth, 358 Mich. 447; 100 N.W. 2d 486 (1960)

Kadzban v Grandville, 442 Mich 495; 502 N.W. 2d 299 (1993)

Kuick v Grand Rapids, 200 Mich 582; 166 N.W. 979 (1918)

Lawrence v City of Grand Rapids, 166 Mich 134; 131 NW 581 (1911)

McIntosh et al v city of Muskegon, 88 Mich App. 30; 276 N.W. 2d 510, 511 (1979)

Niles v Meeker, 219 Mich 361; 189 N.W. 207 (1922)

Rema Village Mobile Home Park v Ontwa Twp, Michigan Court of Appeals, Case No. 256395, unpublished (2005)

Reschke, E. and Turner, J. 2009, Special Assessment Course Text, Westphalia, Michigan; Michigan Assessors Association

St. Joseph Twp v Mun. Finance Comm, 351 Mich 524, 533; 88 N.W. 2d 543

State of Michigan, 2002 SAB Assessor’s Training Manual, Ch 13, http://www.michiganpropertytax.com/Chapter%2013%20SABmanual.pdf (Accessed Dec. 7, 2012)

Williams v Mayor of Detroit, et al., 2 Mich 560, 5; WL 3638 Mich (1853)

70 Am Jur 2d, Special or Local Assessments, Apportionment between public and property benefited, §84

About the Author Joseph M. Turner, MAAO, holds an Associate in Science Degree from Delta College, a BA degree from Saginaw Valley State University, and a certificate in Real Estate with academic distinction from University of Michigan’s School of Business. He is also Chairman of the city of Saginaw’s property tax Board of Review and owns a consulting company, Michigan Property Consultants L.L.C.